Visitors today might think of Raby Castle as a ‘museum’, but this is not the only time in its history where it has been considered as such. In the first half of the 19th century, Elizabeth (c.1777-1861)—the second wife to the 1st Duke of Cleveland (1766-1842)—compiled at Raby ‘a most curious Museum of Natural History, collected with much care, skill and attention’ [1]. This museum, however, was not to everybody’s taste. Nor did it survive beyond the mid-19th century. During 2020, Raby intern Dorothea Fox has studied the collection at Raby Castle as part of her postgraduate studies at Durham University. Here she reflects on her findings and what they tell us about Raby’s past.

Elizabeth (c.1777-1861), 2nd wife of the 1st Duke of Cleveland who established a “most curious Museum of Natural History” at Raby Castle.

So what happened to Raby’s Museum of Natural History? It is likely that the collection of ‘museum’ objects was disassembled during restoration work between 1843-1850. After that time, the taxidermy and natural-history collection were moved from room to room until a suitable home could be found for them. The movement of these objects was recounted by the 4th Duchess of Cleveland in her Handbook to Raby Castle. This year marks the 150th anniversary since the publication of her guidebook—an important resource to understanding the history of the house.

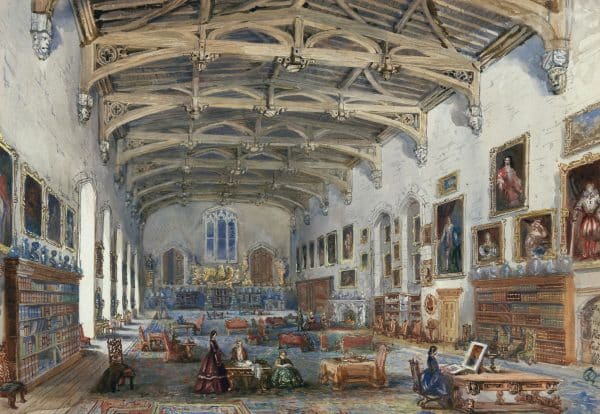

The 1st Duchess’s museum was located in the Barons’ Hall. With dimensions of 132 feet by 36 feet by 32 feet, this was an impressive space in which to exhibit her natural-history collection. Not only that, but the space carried with it the powerful memories of former times. In many accounts, it is noteworthy for entertaining 700 knights and retainers of the Neville family at once, and for being the site where, on 13 November 1569, a great council of northern nobles decided upon an insurrection against the Crown—the fatal ‘Rising of the North’.

By the time of Raby Castle’s 1842 inventory, there is a sub-heading, ‘The Museum’, under the section on the Barons’ Hall. It is described as ‘consisting of various glazed cases of specimens of Natural History, Cabinets, Indian Curiosities, and Oriental Porcelain’. An article from 1833, which featured in the American women’s magazine, Lady’s Book, sheds more light on the diverse objects:

‘The rough inmates of the forest, harmless as the fierce barons who once feasted beneath the fretted roof, are chained in mimic life to guard the doors. Handsome glass cabinets are arranged around the walls, enriched with all that mineralogy can yield, mingled with shells, fossils, bones, dried specimens of animal and vegetable life, works of art, and relics of the olden times. Several articles connected with the worship of the Catholic Church are here preserved. Amongst others, a curious cross, or rood, as it was anciently called, and a spoon set with precious stones, doubtless formerly used in the ceremony of consecration.’ [2]

While the author of this account is unknown, the castle and its museum were clearly deemed of interest to an American audience: whether as visitors or as readers of the magazine.

Displaying ‘natural’ matter alongside ‘cultural’ artefacts corresponds to the idea of the ‘cabinet of curiosity’. Across Early Modern Europe, collectors, curators and visitors were driven by inquisitiveness into objects that were rare and unexpected, producing eclectic wunderkammer—cabinets of wonders. While some private collectors like Duchess Elizabeth continued these practices, from the 18th-century ‘Enlightenment’ period there was a shift towards more narrowly-focused displays, paralleling the development of public museums and a division between the ‘arts’ and ‘sciences’.

But the cabinet of curiosity still presented a form of intellectual stimulation to those who were excluded from ‘academic’ study, particularly women. Processes of collecting and arranging nurtured their creativity, using the patterns and details of nature as a guide to aesthetic harmony. Moreover, it brought knowledge of science, archaeology, art and religion to bear on decorative practices, enabling women to engage with these subjects in a manner that was considered socially acceptable.

Historic display of tropical birds which probably formed part of the 1st Duchess’s museum. Still on show at Raby Castle.

The Portfolio magazine praised Duchess Elizabeth for these wider implications of her museum:

‘[she] has devoted a great portion of her attention to Improvements both in the castle and grounds, and has gone to considerable expense and labour in the formation of a museum, which bids fair to rival any private collection this country has to boast.’ [3]

There was logic in her transformation of the Barons’ Hall into a display room—a museum. Since its inception, the room was a decidedly public space. As a ‘medieval hall’, it would have received guests and followers; a single, open room in which people ate, entertained and slept. From the late eighteenth century, the Romantic movement revived an interest in medieval halls, converting them to suit contemporary purposes. The nineteenth-century architect, Augustus Welby Pugin, was anxious to restore these ‘capacious’ spaces so that the aristocracy ‘might exercise the rights of hospitality to their fullest extent’: where noble and humbler visitors ‘partook of their share of bounty dealt to them by the almoner’. [4]

Within the Barons’ Hall, therefore, noble hosts were expected to perform public acts of generosity and chivalry. These behaviours were thus adapted to the circumstances of the 1st Duchess. She demonstrated aristocratic munificence by offering an abundant, multicultural cornucopia—her own miniature world in which the diverse relics of natural and human history were assembled and made visible under glass cases.

Not all visitors, however, approved of Duchess Elizabeth’s curatorial vision. In 1828, The Sporting Magazine cautiously remarked that ‘[the Barons’ Hall] is now filled with all the curiosities of the mineral, vegetable, and animal world; but on this subject I am silent.’ [5] Meanwhile, the historian-tourist William Howitt, in his Visits to Remarkable Places (1842), complained that:

‘this hall, which should only display massy furniture, suits of armour, and arms and banners properly disposed, is converted into a museum of stuffed birds, Indian dresses, and a heap of other things which may be better and more numerously seen elsewhere. In fact, any ordinary room of this many-roomed castle might have served this need.’ [6]

Howitt clearly believed that this space should have been treated with utmost veneration for its medieval origins; glass cabinets of birds, insects and shells seemed out of place. This may relate to the ‘professionalisation’ of history across the nineteenth century, during which the boundaries of ‘history’ were demarcated from other subjects, such as those that came to be classified as ‘science’.

It is not certain when the museum was dismantled, but, as mentioned above, it probably coincided with the architectural renovations of 1843-1850. Elizabeth’s successor, Catherine Lucy Wilhelmina, the 4th Duchess of Cleveland, documented her criticisms of the natural history collection in her Handbook to Raby Castle (1870)—a guide to the house, its history, its contents and its inhabitants. This is despite the fact that the 4th Duchess never saw the museum in its intended layout.

Catherine Lucy Wilhelmina (1819-1901), 4th Duchess of Cleveland and author of the Handbook to Raby Castle.

Throughout the Handbook, the author implies a curatorial conflict with her predecessor. While the 1st Duchess lavished care and attention on the objects she compiled—valued so highly, they were granted ‘museum’ status—the 4th viewed them as something of a burden. Her relationship with the natural-history objects, and her efforts in rearranging them outside of a ‘museum’ context, were partially recounted in the Handbook.

The natural-history collection posed a formidable problem: how could the 4th Duchess integrate these objects into the lived-in spaces of the castle? She made no attempt to re-establish the Baron’s Hall museum—a decision which seemed to correspond to her belief that ‘the chief interest of Raby consists in its bringing so visibly before one of the long-past ages of feudalism’.

Accordingly, the Handbook pays special attention to listing the ‘gallery of fifty-four portraits, consisting almost entirely of family pictures’ in the Barons’ Hall. This was a product of the 4th Duchess’s direct curatorial intervention: ‘I found almost all these pictures taken down and piled up against the sides of the room, and felt the task of re-hanging them rather a weighty responsibility.’

The Barons’ Hall, Raby Castle, mid 19th century. This watercolour must have been painted not long after the museum was disbanded.

The 4th Duchess frowned upon the former arrangement of natural-history objects here, fashioning the Baron’s Hall into a ‘receptacle for all kinds of lumber’. She deplored the ‘old Duchess’ who ‘had even the common swans and foxes brought in to be stuffed’—native animals that possessed no value in peculiarity. She also ‘felt a positive regret at the money which … had been spent upon shells alone.’

In designating the 1st Duchess’s museum as ‘lumber’—cluttered odds and ends—the 4th separates herself from the then out-dated practice of the wunderkammer. In contrast, her priority for the Barons’ Hall was to draw attention towards its medieval connotations and its significance in the history of the family.

An assorted collection of natural and cultural objects might have appeared harmonious to Elizabeth, but in the eyes of Catherine it was a ‘great array’ of incongruous and indiscernible things—in stark contrast to her own vision for the Barons’ Hall. Her Handbook can help to reveal to the afterlives of some of the natural-history objects once they had been removed from the Baron’s Hall. In what must have been a temporary measure, 51 cases of ‘preserved birds, animals and insects’ found their way into the Stucco Anteroom—a space that is minuscule in comparison with their previous home.

Unwilling to leave the anteroom ‘crammed with stuffed birds and beasts’, the 4th Duchess removed some to the Smoking Room, which they overflowed, and from there to ‘various remote and unfrequented parts of the castle’. In these dark and mysterious corners of the house, she left them ‘dwelling in strict retirement’. We also learn that during the time of the 2nd Duke, ‘three cartloads of spars and crystals’ were put into storage in the Bath House, situated about 800m south-west of the castle.

Other specimens and remains were simply given away: the 4th Duchess writes that she ‘was fortunate enough to dispose of [them] as presents to neighbouring amateurs.’

Not all of the animal, vegetable and mineral matter met the same fate. The Handbook mentions three stuffed creatures which its author managed to reconcile with her decorative arrangements for the Entrance Hall and Corridor: a platypus, a polar bear and a small crocodile. Some visitors may still remember the crocodile, which continued to inhabit the Entrance Hall into recent times.

Historic natural history displays at Raby continue to be appreciated as rooms are refurbished.

The story of Raby’s ‘Museum of Natural History’, therefore, is the story of two women—the 1st and 4th Duchesses of Cleveland—who took vastly different stances on value of these objects. In their divergent ways, these women demonstrated their aesthetic and intellectual visions for the castle.

The precise whereabouts of the huge natural-history collection compiled by the 1st Duchess is still something of a mystery; although glimpses can be found in the castle collections today. Even more of a mystery is what actually constituted the ‘Museum of Natural History’: what exactly were all the specimens, artefacts and remains that were once displayed in the Baron’s Hall museum? To trace the lives of these objects, animals and specimens—where they came from, when and how they entered Raby’s collection, and what happened to them after the disbanding of the ‘museum’—would certainly be an exciting journey of discovery.

If you enjoy discovering the stories behind Raby Castle and its fascinating collections, a Raby Membership gives you free access to the Castle, Park and Gardens for 12 months.

References:

[1] Neale, J.P. (1818), Views of The Seats of Noblemen and Gentlemen, in England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland, Vol. I., London: W.H. Reid, np.

[2] ‘Raby Castle’, Lady’s Book, June 1833, p.280.

[3] ‘Antiquities of Great Britain. No. II.’, The Portfolio of Amusement and Instruction in History, Science, Literature, the Fine Arts, &c., 14 October 1828, No.21, p.331.

[4] Pugin, A.W. (1841), True Principles of Pointed or Christian Architecture, London: Henry G. Bohn, p.61.

[5] ‘Nimrod’s Yorkshire Tour’, The Sporting Magazine, January 1828, Volume. 21, No. 71, p.203.

[6] Howitt, W. (1842), Visits to Remarkable Places: Old Halls, Battle Fields, and Scenes Illustrative of Striking Passages in History and Poetry: Chiefly in the Counties of Durham and Northumberland, London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, p.258.