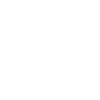

We caught up with Annie Garthwaite ahead of her debut book launch to find out more about her heroine, the fascinating Cecily Nevill. Cecily was born at Raby Castle in the 15th-century and lived through the famous historical period of the War of the Roses. Born a Lancastrian, but a Yorkist by marriage, Cecily had to navigate the challenging political landscape of medieval England. Becoming a mother to two kings of England she was always close to the throne, but never highlighted as a key player. We want to delve deeper to bring Cecily’s story to light and find out more about the woman who once walked the halls of Raby.

What inspired you to write about Cecily? Why is she such an interesting character?

It started in school. My comprehensive wasn’t the most progressive in the world, but I was blessed with a wonderful history teacher, Keith Hill. It was The Wars of the Roses for ‘A’ Level and the stand out figure for me then was Cecily’s youngest son, Richard III – the hunchback, the tyrant, the child-murderer. I was about to write him off. “Was he though?” Keith asked. “Who says so?” That’s when the link between ‘history’ and ‘story’ became clear to me. Stories shift depending who is telling them, the past is the ‘raw material’ of story, open to interpretation, investigation, retelling. “Read that,” said Keith Hill and lobbed a copy of Rosemary Hawley Jarman’s novel We Speak No Treason, at me. It gave me a new Richard. Not a murdering tyrant, just a man making hard decisions in tough times. I was entranced.

As I got older though, it was the strong women around Richard who captured my interest – Marguerite of Anjou, Margaret Beaufort, Elizabeth Woodville. But one woman kept eluding me. Richard’s mother, Cecily. Where was she?

Well, you might say Shakespeare ‘did for Cecily’, no less than for her son. Her appearances in his history plays are brief. She has no political agenda, exercises no power and serves no dramatic purpose other than to curse her misbegotten offspring. Shakespeare’s Cecily is old, pious, embittered and dull, and that damning characterisation has, unfortunately, has stuck.

Nothing could be further from the truth of course. Cecily lived through eighty years of tumultuous history, close to the beating heart of power. She mothered kings, created a dynasty, brought her family through civil war. She met victories and defeats in equal measure and, in face of all, lived on. Last woman standing. How could I not want to tell her story?

What was Cecily’s life like growing up at Raby?

Raby was, of course, the principal seat of Cecily’s family and would have been her home growing up. She’d have felt secure here, I imagine, at the heart of a powerful family with close connections to the Crown. During her time at Raby her life expectations would have set; an advantageous marriage, a position of power, a close relationship to the crown.

Cecily’s mother, Joan Beaufort, was Henry IV’s half-sister (they shared a father in John of Gaunt). Her father was Ralph Earl of Westmorland, one of the first of England’s nobility to support Henry IV’s bid for the throne and his deposition of Richard II. It seems to me that Ralph’s prestigious marriage to the king’s half-sister was, at least in part, a king’s reward for Ralph’s support. So, I think Cecily would have grown from childhood to understood that support for the Crown would be rewarded with security and prestige. It’s ironic, too, that she was brought up in the heart of a Lancastrian family at Raby, though she was destined to become matriarch of York, Lancaster’s rival in the Wars of the Roses.

This window seat at Raby Castle is sometimes referred to as the Rose of Raby Room after Cecily

How were Cecily and Richard Duke of York betrothed, and what was their relationship like during the course of their marriage?

Cecily’s was arguably the most brilliant of a series of dazzling marriages that Ralph and Joan made for their children. Cecily was married late in 1423 at the age of eight to Richard Plantagenet, heir to the earldom of Cambridge and dukedom of York. It was a promising match, but not without risk for, as well as being heir to prestigious titles, Richard was also the son of a traitor. His father, Richard Earl of Cambridge, had been executed by Henry V in 1415 for his part in the Southampton plot. To secure his inheritance, the young Richard would have to win the favour of the present King Henry VI. Unless Henry confirmed Richard’s titles at his coming of age, he would not receive them and Cecily’s brilliant marriage would have lost its lustre. One can only imagine that Ralph took upon himself a mission to make a ‘king’s man’ of Richard, to imbibe him with Lancastrian loyalties, to ensure his smooth accession to his titles and, effectively, co-opt the wealth and prestige of those titles into his own family.

Two years later, both the brilliance of the marriage and its risks became greater still. When Richard’s maternal uncle Edmund Mortimer, the fifth earl of March, died childless in 1425, Richard became heir to a vast Mortimer inheritance. All good. However, that inheritance also brought with it a claim to the English throne that rivalled that of the present king. Henry VI took his royal claim from Edward III’s third son, John of Gaunt. Richard, meanwhile, could claim direct descent from Edward’s second son, Lionel Duke of Clarence, and his fourth, Edmund Duke of York.

The fact of Richard’s royal claim dogged their married life and though conspicuously loyal to Henry VI, Richard was always under suspicion. Despite this, Cecily’s closeness to Richard is evident. They spent time together whenever possible and she accompanied him on his travels to France and Ireland when royal duties took him there. She bore him twelve children, lost five in infancy, but succeeded in bringing four sons and three daughters to adulthood. She had a long wait for children, however. Though Richard and Cecily began their married life together in around 1431, she had to wait eight years, until 1439, to deliver a living child (a daughter, Anne) and another three to bring forth a son (Edward) that survived infancy. This must have been challenging. Of the many demands placed upon a medieval aristocratic woman, the greatest was to bear children. But there is no evidence that Cecily’s early failure in this regard led to any fracture in her marriage. She and Richard appear to have remained close during this time and, since there is no evidence that Richard owned any bastards, it seems likely he was faithful or, at least, discreet. Fortunately, after a slow start, Cecily’s childbearing potential – and her ability to deliver strong sons – became one of her most valuable assets.

As Richard’s loss of royal favour became increasingly serious, Cecily shows every sign of striving to revive it. Like Richard, she seems to been at pains to persevere in loyalty to the crown for as long as possible. In 1453, for example, she petitions Queen Marguerite on her husband’s behalf, begging no favour but that he be returned to the king’s good graces. However, it seems to me that, as matters progressed from bad to worse, Cecily must have come to recognise that she and Richard faced a stark choice – either to take power or be destroyed by it. As a wife and mother, and as a woman of high noble birth, I can well imagine she might have reached the conclusion that the only place of safety for her husband – and by extension, her sons – was on the throne.

Depiction of Cecily in the Chapel at Raby Castle

What was Cecily’s character like?

Cecily is often referred to as ‘Proud Cis’. I can see why, but it’s too simple. Pride infers a certain arrogance and disdain that I don’t think was part of her character. More accurately I would say that, by the time she left Raby as a married woman at the age of around 15, Cecily would have understood her privileged and prestigious place in the world very well. She was aware and justifiably proud of both her parentage and her marriage, ready to make the most of her advantages as one of England’s principal ladies. Having come from one family that held itself close to the crown, she’d have felt ready, I think, to embark on the serious work of creating another. Everything I’ve learned about Cecily suggests to me that her intention was to raise a family that would continue to serve the royal house of Lancaster. Why not? And only when her hand was forced by circumstances and the weakness of Henry VI’s rule did that change.

Which other locations did Cecily travel to and live over the course of her lifetime?

Cecily’s time at Raby was, in fact, quite short. She left her childhood home in 1430 when she was about 15 years old and never lived there again. She and Richard had vast estates across England, Wales and Ireland so, as for many medieval nobles, their life was fairly peripatetic. However, they spent a good deal of time in two key locations, which seem to have acted as their headquarters. From Fotheringhay in Northamptonshire they managed their English estates. From Ludlow on the Welsh borders, they managed their lands in Wales and Ireland. Several of her children were born (and sadly buried) at Fotheringhay as are, of course, both Cecily and Richard. In her widowhood she tended to stay closer to London, either in her town house of Baynards’ Castle on the Thames or in various locations around Suffolk where, it seems, she enjoyed the company of a community of intellectual women. She, of course, also spent time with Richard in France – Rouen for the most part – and in Ireland, and visited the Burgundian Court on at least one occasion.

Throughout her life, Cecily embodied many different roles such as a daughter, a sister, a mother, a wife, a duchess, a friend and rival – how did she establish her loyalty at a time when friends and family were on opposing sides?

It seems to me that the great drama of Cecily’s life stems from the fact that she is born into Lancaster and marries into York. It begs a question we all have to answer in our own lives, I think; which family owns our greatest loyalty, the one we’re born into or the one we marry into?

Cecily’s loyalty to Richard and their children over-rode all others, but it can’t have been easy. It always seems particularly poignant to me that Humphrey Duke of Buckingham, the husband of Cecily’s sister Anne, was killed in battle fighting against Cecily’s son at the Battle of Northampton. Anne was nearest in age to Cecily and they seem to have been close. Moreover, Cecily was with Anne when news of Humphrey’s death was brought home to her. Imagine; two sisters, one rejoicing in her son’s victory, the other mourning the death of her husband. It’s one of the scenes in my book I found most challenging to write.

I’ve heard the Wars of the Roses described many times as the greatest of all family squabbles. It was exactly that, and Cecily always at the heart of it. But it seems to me that, once she realised that the only way for her husband and children to be safe was to take the throne, she was determined to set all other considerations aside to achieve that goal. Some people might call that ruthless but, actually, I think it’s a mother’s natural instinct to defend her children at all costs. In that regard at least, Cecily isn’t so different from other women.

Raby Castle, Cecily’s childhood home

At a time when women’s roles were limited and men were in positions of power, how did Cecily use her influence and navigate her way to achieving her ambitions?

It’s easy to assume that women in the middle ages had little power or influence. In fact, that’s not the case. Medieval women, especially those of the aristocracy, or in what we might today think of as the middle classes, had freedoms their Victorian counterparts, or even my own post-war mother, could only dream of. They could own property, run businesses, take up trades. Widows especially could achieve significant economic independence. Men ruled, certainly, but in the margins, women could exercise agency, assume authority, push boundaries. Women of Cecily’s status, with huge households and vast estates, would be responsible for enterprises similar in size and complexity to mid-sized FTSE companies. They would be highly literate, understand finance and the law, have a firm grasp of politics. They’d be, in short, women of business. At the same time, they’d be expected to support their husbands’ political careers and advance her family’s interests within intricate and hierarchical social networks.

Cecily was adept at all these things and, certainly, appears to have been a trusted confidant and advisor to both her husband and her kingly sons. In the early days of Edward IV’s reign foreign ambassadors wrote home to their masters that Cecily ‘could rule the king in all things’ and that, if they wanted to do business with England, they would have to do it first with Cecily. Historians note that Cecily seems to have emerged as a political power to be reckoned with after Richard’s death. That’s true, but I like to think she sharpened her skills working at Richard’s side. I see them as perfectly matched in intellect, ambition and skill and, when he died, she stepped out from his shadow as a confident and adept politician in her own right.

Cecily lived through many horrors during her lifetime. For example, the brutal deaths of her husband and children, watching from the side-lines while family killed family. How did these experiences change her and how did she find the physical and mental will to keep surviving?

Oh, that’s such a tough question to answer! What we do know is that Cecily does survive all of that. She sees her granddaughter become queen of England and seems, to a point at least and in public, to have reconciled herself to Henry VII’s reign. She dies at 80, ten years after the death of her youngest son at Bosworth, outlived by only two of her children.

I think it’s hard for us in the twenty first century to understand how the medieval mind dealt with death and disaster. I sense a struggle in Cecily’s mind always between bending to God’s will and asserting her own. In that sense, at least, she seems to me quite ‘modern’. My mother used to say that God helps those who help themselves, and I think Cecily would have agreed. I’d say she believed in her family’s right to rule, both as a woman of faith and as a pragmatic politician. That means the fall of her family must have shaken her to the very foundations.

It’s intriguing to me that, when her body was exhumed during the reign of her great-granddaughter Elizabeth I, there was found, tied around her neck, a papal pardon penned in fine Roman hand. Cecily must have acquired that pardon during her lifetime, and paid good money for it too. She must have believed (or gambled?) that, at the day of judgement, it would allow her to stand before God, if not justified, at least redeemed. Perhaps it was her way of saying that she surrendered to fate of her family and whatever role God’s will might have played in it.

What can we learn from Cecily today?

Too often film and fiction revert to stereotypes when it comes to medieval women. They’re either objects of chivalry, pampered and adored, or they’re repressed voiceless victims. Neither is accurate. In my novel, I’ve tried to deliver a version of Cecily that’s closer to the 15th century truth. Along the way, I realised she’s not too far from 21st century truth either.

For much of my life (I didn’t start writing Cecily until I was fifty-five) I’ve worked in business. For many years I worked for large American multi-nationals. For the last twenty I ran my own business advising them. I often found myself the only woman at the big table, finding ways to get men to do what I wanted, needed or thought they ought to do. I think Cecily had those skills in abundance and could have taught me a thing or two!

Yes, Cecily was a woman of her time – of a pre-reformation, pre-feminist, Catholic, male-dominated world. But she was also a woman we can feel kinship with today; fighting with words when swords were denied her, exercising whatever authority was given to her and always pushing for more. Testing boundaries, holding her own. She faced many of the questions women still struggle with today. What comes first, love or ambition? How do we protect our family? How far will our courage take us?

If you could go back in time and ask Cecily herself one question, what would it be?

Just one? That’s tough! Okay, it would be this: ‘Cecily, where are your grandsons?’

We all know that Edward IV’s sons ‘disappeared’ from the Tower in the early years of Richard III’s reign. What happened to them next is one of English history’s greatest mysteries. I’d love to know what Cecily knew about it. Although perhaps, in the end, she knew no more than you or I.

Annie Garthwaite’s debut novel, CECILY was published by Penguin on 29 July 2021 and is available in our Stables Shop at Raby Castle.

Raby Castle and our Stables Shop are currently open Tuesday – Sunday from 11am.

If you’d like to visit Cecily’s childhood home and find out more about the Nevill family, book a Castle, Park and Gardens ticket.