World Pharmacists Day, September 25th

In celebration of World Pharmacists Day, we’ll be looking at an interesting item which was found nestled in the back of one of Raby Castle’s many cupboards, shedding light on the way that sickness and injuries were treated in historic country houses.

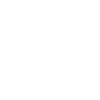

An unexpected discovery was made over the winter period at the castle, as Raby’s Curation and Archives team were busy auditing the collections while the castle was closed. A cupboard drawer was opened one day, and an unassuming wooden box was spotted. Upon opening, it turned out this box in fact contained a fascinating at-home medical collection. This included a selection of medicines- some liquid in glass bottles, other in powder and pill form- some weighing scales and measures, and a glass pestle and mortar.

What followed was a concerted effort to catalogue, research and conserve the item, so it could be preserved and understood for future use.

Research

Britain has a long tradition of self-medicating, from growing herb gardens since the time of the Romans, to medical knowledge being passed down through family recipes, and owning these medicine chests which could be described as historic ‘first-aid kits.’

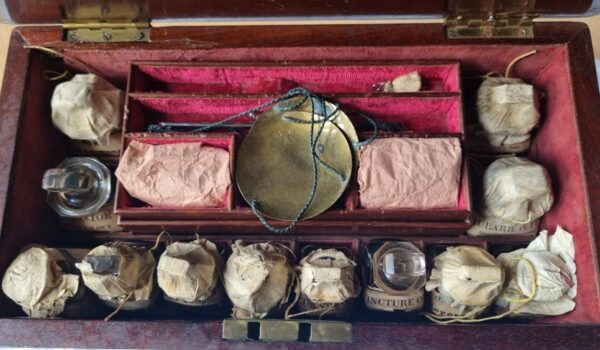

Medicine chests reflect a period of change, as towards the end of the 1700s medical texts began to be written in a language the general public could understand, and readymade tinctures (a medicine made by dissolving something in alcohol) and powders made medicine more accessible and affordable. Once bottles were empty, they would be refilled and re-labelled by a pharmacist.

The chests also contained tools used to self-medicate. This included scales, a set of apothecary weights in units such as drams and grains, and a pestle and mortar to grind ingredients.

Some contained instruction manuals which explained how the ingredients should be used and in what doses. Unfortunately, ours didn’t come with an instruction manual, but pharmacist John Savory created a helpful one with detailed instructions for many of the medicines found in our box.

Savory and Moore

The glass bottles in our medicine box have labels for Savory & Moore or Savory, Moore & Sons. Savory and Moore were a pharmacy company, founded by Thomas Paytherus in 1794. Thomas Savory joined the company in 1797, and in 1806 he became partners with (another) Thomas Moore.

They were originally based at 136 New Bond Street, then 143 Bond Street from around 1840, (it could be that 136 was re-named 143 Bond Street) which helps us when trying to date the bottles in our collection- these are labelled as 136 New Bond Street and 220 Regent Street. A network of pharmacies was created from 1849 onwards, which could explain the additional address. Savory and Moore became the official suppliers of the War Office and the Royal Family, also seen on the label.

In 1968 the shop was closed, and the fittings and contents were given over to the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine. In 1992 Savory and Moore was taken over by Lloyds Pharmacy.

Medicines

The Raby chest contains some interesting medicines which tell us a bit about health and society during the mid-to-late 1800s. These include:

- Sal Volatile: Smelling Salts

Found in everyone’s medicine box during the Victorian period, smelling salts were used as a stimulant to restore consciousness after fainting.

- Purgatives

It was popular throughout the 19th century to induce sweating, vomiting or diarrhoea as a means of treating several illnesses- to ‘purge’ the body. This was done using several remedies in the medicine chest.

Rhubarb, specifically the root of Turkey Rhubarb, was used as a strong laxative. John Savory, in his ‘Companion to the Medicine Chest’ in 1836, states ‘the medicinal properties of this valuable root are so well known, that it appears to almost a work of supererogation to mention them. It is administered in the forms of powder, infusion, and tincture.’

He also suggests Senna as a ‘very useful and very general purgative, there being scarcely any disease in which it cannot be administered. It is customary to disguise the nauseous taste of senna…’

- Familiar: Castor Oil

There are some names, such as Carbonate of Soda and Castor Oil, which it wouldn’t be unusual to see in a kitchen cupboard today. Savory talks of cold drawn Castor Oil “This oil is a valuable aperient; for whilst, in doses of from half an ounce to an ounce, it thoroughly evacuates the bowels, it does so with little irritation; hence it is especially useful in inflammatory cases… One disadvantage attending the use of this oil is its tendency to excite vomiting, but this is counteracted by combining it with some aromatic… Upon the whole, castor oil is a purgative of great value.”

- Unfamiliar: James’s Powder

James’s Powder, or ‘Dr. James’s Fever Powder’, was one of the most successful patented medicines from the mid-eighteenth century to the early twentieth century. The medicine claimed to ‘cure most complaints that are not mortal, or chronical’. Several attempts were made to understand the formula, and it was believed to have contained antimony- once used to induce vomiting, but now known to be poisonous- and calcium phosphate. It was never proven effective and is now considered a form of ‘quackery.’

Conservation

The box was then handed over to our Conservation Placement Student. Davina’s first step was to create a conservation proposal, which included a thorough object description, detailing the materials involved. This item was interesting to a conservator because the range of materials there were to work on, such as the rosewood box, copper alloy hinges and handle, textile lining and glass bottles with leather lids.

She then assessed the condition of the item: the box exterior had a break in the wood with evidence of historic repair, the interior fabric was dirty, and some corrosion was present in the metal. There was also the risk of potentially hazardous substances to consider.

Finally, Davina offered her proposed conservation treatments and got to work. She surface cleaned the contents, such as the glass bottles and measuring equipment, and removed the historic adhesive from the broken section of the medicine box. Using a sympathetic adhesive, she mended the break before adding pigments to colour match the mend with the item.

Cataloguing

Our Collections Intern, Rebecca, was then responsible for photographing and recording the item before adding it to our Collections Management System. This would enable us to locate the item in the future once it was safely packed away, if we wanted to use it for a display, talk or further research.

Archives

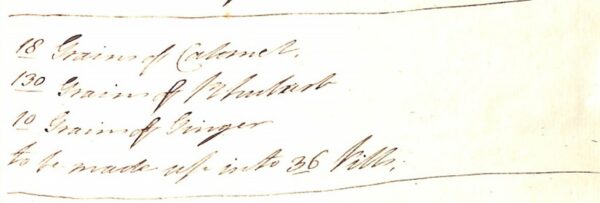

Research into the chest was supported by documents found in the castle’s archives. As previously mentioned, medical remedies were passed down through families. In the Raby collection we have a series of receipt books, which often had food recipes on one side and medical recipes on the other.

One recipe in ‘Mrs. Vane’s Receipt Book’ instructs the reader how to make Rhubarb calomel pills:

18 grains of Calomel

130 grains of Rhubarb

10 grains of Ginger

To be made into 36 pills.

These could easily be produced with some of the contents of the medicine box. (Do not try this at home!)

Thanks to the meticulous photography of our Collections Intern, we were able to research the history of the item more easily. With the work of our Conservation Placement Student, we have ensured the item can be preserved safely for many years to come, and with the collaboration of our Archivist, we can better understand how the item would have been used in the context of the family. A real team effort!