Back in the 1600’s a young and adventurous Henry Vane, ancestor of Raby Castle’s current Lord Barnard, emigrated to join the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Our curator Julie Biddlecombe-Brown reveals who he was, why he went and what happened next.

First, a bit of background about the Vane family at the time

In 1626 Henry Vane the Elder, MP and official in the Royal Household, bought Raby Castle for the princely sum of £18,000. His marriage to Frances Darcy brought the wealth that secured his rise in Court and should have guaranteed a life of relative ease for their children. This was not to be for his first-born.

Henry Vane the Younger had a remarkable life and witnessed events that shaped nations and the world. His life ended in the Tower of London in 1662, described by Charles II as “…too dangerous a man to let live …”.

We’re going to explore the life of the twenty-something Henry, in Puritan New England, and how his legacy can still be seen today

Henry Vane the Younger was born in Essex in 1613, the eldest of eleven children. Less than one hundred years after the break from Rome, the early 17th century was a time of religious turmoil. Henry was a man of strong religious convictions and by his mid-teens he had made the conscious decision that his faith would play a central part in his life; following his conscience and devotion to God.

After completing his education at Magdalen College, Oxford, he travelled in Europe, where he visited the intellectual Protestant hubs of Geneva and Leiden. His travels continued during his late teens as an aide to the Ambassador at the court of the Holy Roman Emperor, Ferdinand II. On his return to England his prospects seemed bright and it appeared certain that he would follow his father’s career in the royal household. But the young Henry had other plans.

So, what inspired him to make his long and dangerous Trans-Atlantic journey?

He had never lost the spiritual resolve of his earlier teenage years and became increasingly disillusioned with what he viewed as the restrictive ceremonies and practices of the Church of England. Henry looked to the Puritan colonies of the New World as a kind of utopia. Here, he believed he would be surrounded by people who had committed to create the kind of world he aspired to; people with similar beliefs and values. So, in 1635, at the age of 22, with his father’s eventual blessing and a three-year release from court from the King, he emigrated to New England.

Was it everything he expected it to be?

Young Henry arrived in Boston, Massachusetts on 6 October 1635, one of an estimated 20,000 English people believed to have emigrated to New England in the 1630s. He found a community that was developing rapidly and a mixture of settlers, from devout Puritans to commercial entrepreneurs. Governance centred around the church and strict Puritan ideals that occasionally clashed with the commercial activity of the new colony. Henry was made welcome; his background and strong convictions held him in good stead, as did his advantageous connections back in England. He quickly settled into Boston life where his social rank and experience of diplomacy were put to use in in resolving disputes and supporting the governance of a growing community. Within a few months he became a freeman of the Massachusetts Corporation; perhaps more surprisingly, he was elected as Governor in May 1636 at the tender age of 23; the highest office in the colony.

Henry quickly established himself as a leader …

The Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony was elected annually, and Henry set out to use his diplomatic and administrative experience to create new laws and resolve disputes amongst the colonists. During his short time as Governor, legislation was passed to establish a higher education college in the colony; an institution that would later be named after the wealthy clergyman and benefactor, John Harvard.

…although it wasn’t all plain sailing

But Henry’s passionate conviction (probably combined with his youth and inexperience) resulted in a very challenging term as Governor. Tensions were quickly escalating with the local Native American population for whom the impact of the arrival of the European colonists had many devastating consequences. Within the colony the harmonious Puritan utopia that he had dreamed of was becoming fragmented. The relationship became strained between some of the more orthodox members of the community (characterised by Henry’s deputy, John Winthrop), and others who supported greater religious freedoms, including Henry himself.

He made friends with people who held “dangerous opinions”

Two of Henry’s close acquaintances from his short time in Massachusetts provide an insight into Henry’s beliefs and personality. Both Roger Williams and Anne Hutchinson are important, yet controversial figures in the complex history of early English settlement in the New World. Their own stories are fascinating but here we look at their relationship with the young Governor.

Roger Williams was an English clergyman with a firm belief in religious freedom. He was banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1635 for spreading “new & dangerous opinions”, including a belief that church and state governance should be kept separate, and for his disapproval of colonists who confiscated land from Native Americans. On leaving Massachusetts, he purchased land from the Narragansett people to establish the Rhode Island Colony, based on principals of religious tolerance. Ten years Henry’s senior, Williams’ conscience-led decisions clearly appealed to the young governor who supported him both in the New World and, later, back in England.

Anne Hutchinson became synonymous with a group known as the Antinomian Party. Her lifelong commitment to the Puritan cause and radical ideas meant that when she arrived in New England she began to push boundaries. Contrary to the norm, she led a Bible Study Group – sometime attracting as many as 80 people, in an age in which women were not permitted to take leadership roles. Her classes were perceived as a threat to some of the more orthodox factions of the colony who feared religious separatism. Henry is known to have attended her groups, no doubt attracted once more by the ideals of religious freedom.

However, Henry was an idealist and his days in New England were numbered

This was a step too far for many in the community who regarded his actions as compromising the position of the Governor. It was one dispute that Henry was unable to resolve and he was pressured to make a choice between his position and his ideals. Unsurprisingly his ideals won out; he attempted to resign as Governor, initially citing pressure to return to England before admitting the conflict between his political and spiritual life. He was persuaded to finish his term, but his former deputy, John Winthrop was elected for the year ahead. Anne was banished from Massachusetts and along with around 30 other families followed Roger Williams to the Rhode Island Colony.

Henry left Massachusetts for England three months later, but not before finally opposing the new Governor ‘s legislation to exclude settlers like his friends who were said to hold ‘dangerous opinions’. His time in New England taught Henry valuable lessons and despite remaining a man of strong conviction, in his later life he attempted to focus on politics rather than spirituality in his public life.

The story of Henry’s later years back in England is equally fascinating, but we will save that for another day

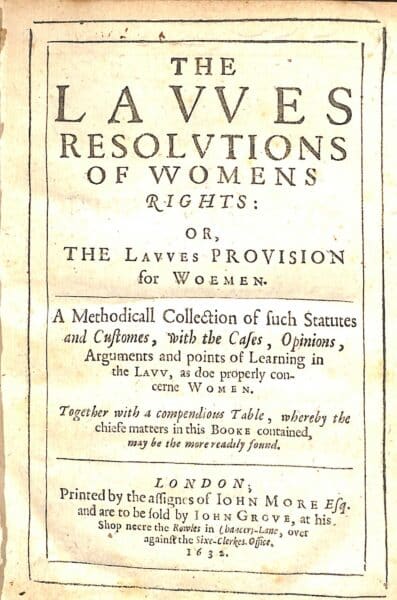

One final note relates to an intriguing item in the castle collections, dating from this period. Pictured here, this little volume titled THE LAWES, RESOLUTIONS OF WOMEN’S RIGHTS OR The Women’s Lawyer. It was printed in London in 1632 and is the first work devoted exclusively to laws relating to women. It covers diverse topics from marriage to land ownership, wooing to widowhood. We don’t know when the book came to Raby Castle but it is interesting to speculate as to whether it, along with other radical 17th century pamphlets, might have belonged to, or have been read by Henry and in this case, how much his encounter with Anne Hutchinson in the New World might have kindled an interest in the law and the position of women in particular.

Julie Biddlecombe-Brown

Sources and further reading:

- Sikes, G., The Life & Death of Sir Henry Vane Kt. 1662

- A Vindication of that Prudent and Honourable Knight, Sir Henry Vane. London: 1659

- Hosmer, James K. Sir Henry Vane. London: 1888

- Mayers, Ruth E. Vane, Sir Henry the Younger. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, May 2015

- N. E. Adamova, S. V. Shershneva, Discourse of early migration to the Massachusetts Bay Colony, 2017

Sir Henry Vane the Younger. Oil on Canvas. School of Robert Walker (1599-1658) ©Raby Estate

Sir Henry Vane the Younger, commemorated in a statue of 1893 in Boston Public Library. The inscription quotes John Winthrop, who despite their differences describes Henry as “a true friend of New England and a man of noble and generous mind”.

The Lawes, Resolutions of Women’s Rights, or The Women’s Lawyer. London 1632 ©Raby Estate

If you enjoyed this fascinating story from Raby’s past, check out our recent blog on the Grand Entrance Hall at Raby Castle for the Historic Houses Feature Friday campaign.