Raby Castle regularly hosts research placements for students who are training for careers in heritage and curation. Despite the challenges of the past 12 months this tradition continued during 2020, albeit virtually, and we are delighted to share some of the fascinating stories about Raby’s oriental ceramic collection which were uncovered by a group of Chinese students who joined us for a placement as part of their studies, at Leicester University’s internationally renowned School of Museum Studies.

Students Xinyi, Manle, Sijia and Suwei were excited to have the opportunity to study Raby’s fine collection of European and Oriental Ceramics, which is on display throughout the Castle.

Xinyi originates from Jingdezhen, the Chinese porcelain “Capital of China” and has had a life-long interest in ceramic culture and technique. Former archaeologist Sijia was more familiar with China’s more distant past and the placement offered an opportunity to learn about more recent centuries through Chinese and Japanese decorative arts.

A Brief History of the Collection

Generations of the Vane family appear to have collected ceramics from China and Japan – a tradition that continues even to this day. During the earliest years of the 19th century, fellow enthusiast, the Prince Regent (later King George IV) visited Raby with his brother and was treated to a display of the castle’s collection in a specially designed “Chinese Salon”. Some pieces in the Raby collection would have looked very familiar to the Prince, including a stunning set of porcelain model pagodas, identical to a set that he had purchased for his own home at Brighton Pavilion. These striking pagodas remain a firm favourite with visitors to the castle today.

The lesser-known pieces in the Raby collection are equally intriguing and were the focus of closer study by the four students. Each student was supplied with detailed photographs of around 20 items. They researched form, decoration, function and technique, as well as wider stories of manufacture, trade, fashion and export.

Fairytale Characters

In this country, those of us that have grown up with Western traditions might see an illustration of a girl in a red cloak alongside a wolf and know immediately that it represents the fairytale character Red Riding Hood – not so obvious if you haven’t been brought up with that story. The same is true for those who are unable to recognise the many cultural nuances evident in Chinese ceramic decoration. For our four Chinese students recognising what might need explanation to a Western audience brought new meaning to the collections. At the end of her placement, Manle felt that her own cultural identity had brought a greater level of depth to the information that she had been able to share with the Raby team. From our perspective it added rich layers of detail that otherwise may have been overlooked.

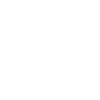

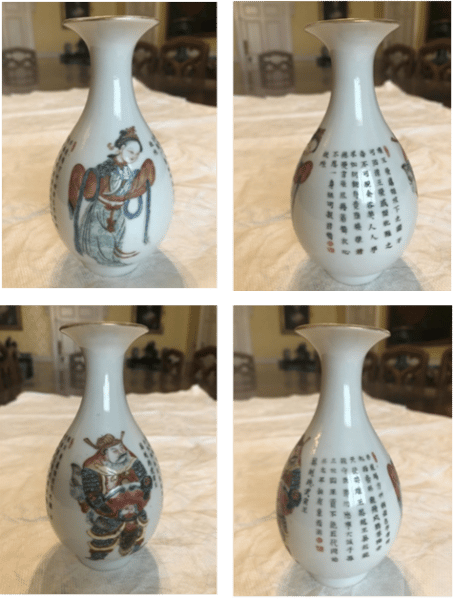

Nowhere is this insight clearer than in one of the pieces depicting Chinese figures and text, researched by student Suwei. Suwei found that the text and the figures on the vase came from the Wu Shuang Pu, or ‘Table of Peerless Heroes’, a 17th century woodblock print containing a collection of beautiful illustrations of historical figures and folk heroes. The two figures depicted on this vase were identified as the male and female folk-heroes Lü Zhu and Qian Liu.

Lü Zhu (ca.250-300), whose name means ‘green gem’, was the favourite concubine of the wealthy Shi Chong. When a powerful General demanded that she be ‘given’ to him, Shi Chong refused and his enemy sent troops to invade to take her by force. Rather than be captured, Lü Zhu chose death rather than submission. The text is a poem that tells of her brave and tragic end.

The male figure, Qian Liu (852-932) was a warlord and the founder of the Kingdom of Wuyue (Nowadays Zhejiang and Jiangsu Province in Southeast China) during the late Tang period. Qian Liu was named the Prince of Yue in 902 with the title of Prince of Wu added two years later. The text is a poem praising of his loyalty to the Tang Empire and his achievements as a local governor.

But in examining the poetry, Suwei spotted a couple of anomalies. Some words and lines of the usual poems were missing. This, she felt, might reflect the fact that these items were being produced on such a huge scale that the painter perhaps chose to omit some words and sentences to speed up the decoration process. We wonder whether anyone before Suwei had spotted this!

Stories of Global Trade

Xinyi was pleased to find that the collection at Raby Castle demonstrated examples of typical cultural exchanges between the two nations. These stories of cultural exchange provide a window on the history of global trade and networks.

Once piece studied by student Sijia, was a “Kraak” porcelain bowl. Her research highlighted the links between “Kraak” (made in Jingdezhen during the Wanli period of the Ming Dynasty 1573-1620) and the Dutch East India Company who brought examples back to Europe for auction as early as 1602. Archaeological excavations in China have helped build understanding of the trade and export of ceramics from this early period, including routes routinely used by smugglers when exports were banned.

This wider history of global trade was researched more fully by Manle, including the background of Chinese export-ware and links between China and Europe during 17th and 18th centuries. This also meant comparing items that were made in China for the domestic market with those that became popular in Europe, looking at interactions between China, Europe and Japan.

A Lasting Legacy

Despite not being on-site at Raby Castle, the four students were able to provide new insight into the pieces they researched, and the castle team were thrilled with what they discovered. Their collective research and the cultural context they shared with the team added layers of rich detail to our understanding of these beautiful items, giving us greater appreciation of the makers and collectors of the past. But what happens next?

This blog shares just a tiny fraction of the information they unearthed. Their research will be added to the castle’s collections database where it can then be used to help to interpret the history of the castle, its owners and collections, their work will help us to create new art tours, and to contribute to exhibitions and art projects.

Although Manle, Xinyi, Suwei and Sijia were not able to visit Raby Castle last summer, we remain in touch with them as they embark on their careers and look forward to welcoming them to Raby Castle when it is possible for them to visit, to see the collection in person.

Other articles you may enjoy:

Our Favourite Things: A Personal Look at Raby’s Collections

Behind the Scenes – The Octagon Drawing Room at Raby Castle

Whatever Happened to Raby’s ‘Museum of Natural History’?