Produced by the Northern Echo in association with Durham County Council

Duncan Peake, chief executive of Raby Estates and a director on the board of Durham County Council’s destination management organisation Visit County Durham, talks to PETER BARRON about the importance of investing in the visitor economy

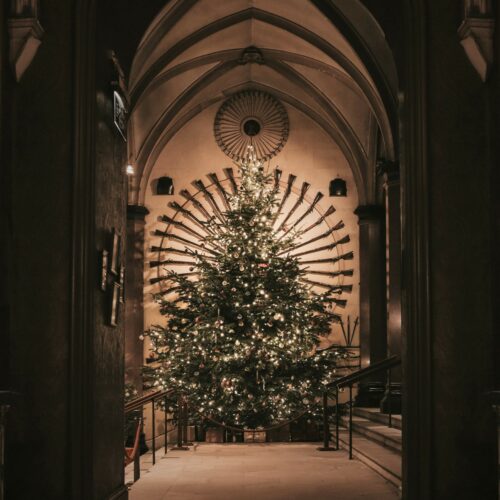

MAGNIFICENT amid the tranquillity of a 200-acre deer park, Raby Castle dates back to the 14th century and yet it stands as an impressive symbol of how County Durham is looking to the future.

And for Duncan Peake, the man charged with plotting the development of Raby Estates, these are exciting times in the history of this stunningly beautiful estate – and for County Durham overall as a visitor destination.

“The opportunities to grow the number of visitors to the county over the next decade are huge because we have an offer that can compete with anything else in the country – and Raby wants to be a special part of that,” he declares.

Duncan, pictured below, is speaking not only as chief executive of Raby Estates, but as a board director of Durham County Council’s destination management organisation Visit County Durham Ltd, and he is passionate about both.

The Raby Castle site is entering an exciting new era thanks to significant investment by Lord and Lady Barnard to enhance the visitor experience. The Plotters Forest adventure playground opened earlier this year, and that will be followed by the opening of the multi-million pound ‘Rising’ development in 2024.

The Rising will restore and preserve historic buildings within the park and gardens, bringing them back to life as contemporary spaces for events and exhibitions, along with a redesigned walled garden, new dining and retail experiences, and visitor information hub.

The development is deeply rooted in history with the restoration and re-use of heritage buildings within Raby Castle at its heart. The term ‘Rising’ was inspired by The Rising of the North, a Tudor Plot, in which the Neville family of Raby Castle played a central part. It also reflects its wider meaning of positivity, growth and improvement. Yet another example of County Durham successfully linking its history and heritage with the future.

“We’ve been overwhelmed by the success of Plotters Forest as the first phase of The Rising – and that’s just the start,” says Duncan.

Lord and Lady Barnard took over the Raby Estate in 2016, with Duncan joining shortly afterwards, bringing a wealth of experience in developing some of the UK’s foremost landed estate businesses.

“Every penny we generate is reinvested into the estate and the local economy,” Duncan explains. “Lord and Lady Barnard’s view is that if we make the fascinating heritage and safe spaces here more accessible, it makes us more relevant to people’s lives and makes Raby more secure as a business.”

Raby Estates also contributes extensively to the community and rural economy. For example, together with the county council-led Digital Durham programme, it has been the driving force behind efforts to bring high connectivity broadband to Upper Teesdale, benefiting both businesses and households.

Gigabit capability is now being rolled out up beyond the famous High Force waterfall, another spectacular feature of Raby Estates, and into Forest-in-Teesdale and Harwood. The improved connectivity will also make a huge difference to businesses such as the newly refurbished Langdon Beck Hotel.

“The more remote communities are, the more reliant they are on decent connectivity,” says Duncan. “So much education resource is now online, and so is a lot of farming and business communication, so it’s vital that the area has the same connectivity that people further down the dale have enjoyed for some time.”

Durham County Council leader, Councillor Amanda Hopgood, is committed to tourism playing a “vital role” in the county’s Inclusive Economic Strategy, which is currently being finalised. “County Durham has something for everyone – glorious countryside, a magnificent coastline, and world-class attractions – with Visit County Durham doing a brilliant job in showcasing our unique offer,” she says.

The county’s latest tourism figures are certainly encouraging. Despite 2021 beginning with a four-month lockdown, Durham welcomed 15.7 million visitors, an increase of 38.5 per cent on 2020. Visitor spend also increased by 63 per cent to £826.68m.

Visit County Durham, the wider council and its partners support tourism businesses with a range of initiatives, including marketing, product development, research, quality improvements, routes to market, and training, and Duncan describes it as “one of the most effective destination management organisations in the country”.

Given his nationwide track record, that’s praise indeed, and he goes on to say: “The cultural offer in County Durham has been underestimated for far too long, but it’s equal to anything in the country when you consider the likes of Durham City, the Durham Dales, the coastline, and attractions like Beamish, The Living Museum of the North, The Auckland Project, The Bowes Museum, and, of course, Raby!

“Visit County Durham is critical in getting the message out to local, national and international consumers that County Durham should be on their list of places to visit. The county attracts lots of day visitors, but we need to attract more people who stay longer, and there’s not enough bed space, so that has to be addressed.

“Potential inward investors should also be aware that in Durham County Council we have a local authority that has an ambitious vision for regeneration and growth. They want to make things happen for investors, so it’s perhaps easier to invest here in County Durham than elsewhere.”

Having supported businesses throughout the pandemic, Visit County Durham now faces the fresh challenge of the cost-of-living crisis. The swift response has been to promote free, low-cost and value for money activities through its ‘Budget Friendly Days Out’ campaign.

It is also attracting visitors into the county through its ‘Memorable Moments’ campaign, which is based around five key themes – family breaks, heritage, the outdoors, culture and food and drink – and is supported by a host of Durham’s biggest attractions.

Visit County Durham is also exploring the increased opportunities within the international market resulting from the uncertain economic climate, with the weak pound making the UK a more appealing holiday destination for tourists from the United States, for example.

At the same time, new tourism products are being developed, such as the Northern Saints Trails, which are expected to attract 85,000 visitors annually between 2022 and 2025, generating a £4.7m yearly visitor spend.

Recruitment is another issue the sector is facing and Visit County Durham is working with further education colleges to address skills gaps and to promote careers in travel and tourism.

It is an area Duncan is especially passionate about, given that it was the career path he chose. He is proud that Raby Estates now employs 105 permanent people plus seasonal employees – nearly double the number six years ago – and there is a strong emphasis on skills development.

“We’re working closely with colleges, we have our own internal leadership programme, and we’re employing apprentices across the estate. Businesses have to develop young people, we can’t just rely on educational establishments and say it’s their problem.”

As the chief executive of a land-based business, sustainability – the theme of the Visit County Durham conference in November – is also high on his agenda.

“It’s a massive issue for us, whether it’s the management of our soils, planting trees, the restoration of peatlands, or promotion of regenerative farming techniques, and it has to be a greater priority for business across every sector because customers will demand it.”

For Duncan Peake, it’s about treasuring the past and making the most of the present, while plotting a sustainable future in which more people grow to love County Durham.

- To find out more about Visit County Durham, go to www.visitcountydurham.org

- To find out more about Raby Estates, go to: www.raby.co.uk

WORKING TOGETHER FOR THE BENEFIT OF All

SANDRA Whitefield is the co-owner of the award-winning Low Urpeth Farm Self-Catering Cottages in Ouston, near Beamish.

“As a Visit County Durham board director, I am a firm believer in the importance of destination management organisations, especially when it comes to supporting small independent businesses.

“In the wake of the pandemic and with the ongoing cost-of-living crisis, this support is more important than ever before.

“Visit County Durham is a partnership organisation within Durham County Council, made up of tourism businesses from across the sector, including visitor attractions, hotels, restaurants and more.

“Around 30 per cent of our partners run self-catering cottages, hostels, inns, bed and breakfasts and guest houses, which demonstrates the major role we play in County Durham’s visitor economy.

“We are all unique and this in turn provides more choice for visitors.

“And while there is an element of competition, we are united in our desire to develop County Durham as a destination.

“At Visit County Durham, we work together for the benefit of all. Whether that be through national and international marketing campaigns or hosting training sessions and conferences on topical issues.

“We also connect businesses with the skills and materials needed locally. At Low Urpeth, for example, we provide guests with Durham Coffee, South Durham Honey and treats from La Chocolatrice. It’s about ensuring the money we spend stays in County Durham.”